New College, Oxford

| New College | |

|---|---|

| University of Oxford | |

The chapel and the old quadrangle | |

Arms: Arms of New College Oxford (arms of William of Wykeham): Argent, two chevronels sable between three roses gules barbed and seeded proper. | |

| Scarf colours: brown, with two equally-spaced narrow white stripes | |

| Location | Holywell Street and New College Lane |

| Coordinates | 51°45′15″N 1°15′05″W / 51.754277°N 1.251288°W |

| Full name | St Mary's College of Winchester in Oxford |

| Latin name | Collegium Novum/ Collegium Beatae Mariae Wynton in Oxon[1] |

| Motto | Manners Makyth Man |

| Founder | William of Wykeham |

| Established | 1379 |

| Named for | St. Mary |

| Sister colleges | King's College, Cambridge |

| Warden | Miles Young[2] |

| Undergraduates | 430[3] (2023) |

| Postgraduates | 360[3] |

| Major events | Commemoration ball |

| Grace | Benedictus benedicat. May the Blessed One give a blessing Benedicto benedicatur. Let praise be given to the Blessed One |

| Endowment | £347.7 million (2021)[4] |

| Website | www |

| Map | |

New College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford[5] in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1379 by Bishop William of Wykeham in conjunction with Winchester College as New College's feeder school, New College was one of the first colleges in the university to admit and tutor undergraduate students.

The college is in the centre of Oxford, between Holywell Street and New College Lane (known for Oxford's Bridge of Sighs). Its sister college is King's College, Cambridge. The choir of New College has recorded over one hundred albums, and has won two Gramophone Awards.

History

[edit]Despite its name, New College is one of the oldest of the Oxford colleges; it was founded in 1379 by William of Wykeham, Bishop of Winchester, as "Saint Mary College of Winchester in Oxenford", with both graduates and undergraduates.[6][7][8] It became known as "New College" because there was already a college dedicated to St Mary in Oxford (Oriel College).[9]

Foundation

[edit]In 1379 William of Wykeham decided to found a college. He applied to King Richard II for a royal charter permitting the foundation.[10] In addition, he wrote a charter of his own, requiring his college to have a warden and seventy scholars. He purchased the necessary land in separate lots from the City of Oxford, Merton College and Queen's College. The area had been the City Ditch, a dangerous place by the city's wall; it had been used within living memory for burials during the Black Death.[11]

The college was founded the same year in conjunction with a feeder school, Winchester College (founded 1382, opened 1394).[7][12] The two institutions have striking architectural similarities: both were the work of master mason William Wynford.[13] The first stone was laid on 5 March 1380. The college had occupied the buildings by 14 April 1386.[14] William of Wykeham then drew up the statutes of the college.[7] The coat of arms of the college is William of Wykeham's. It features two black chevrons, one said to have been added when he became a bishop and the other possibly representing his skill with architecture, since the chevron was a device used by masons. Winchester College uses the same arms.[15] The college's motto, created by William of Wykeham, is "Manners Makyth Man".[7]

New College was established to have prayers said for William of Wykeham's soul. He instructed that there were to be ten chaplains, three clerks and a choir of 16 choristers on the foundation of the college.[16]

As well as being one of the first Oxford colleges to take undergraduates and to appoint tutors to teach them,[8][17] New College was the first in Oxford to be deliberately designed around a main quadrangle.[17] The college was about as large as all of the (six) existing Oxford colleges combined.[18][19]

Civil wars

[edit]The Royalists used the cloisters and bell tower to store munitions early in the English Civil War. In August 1651, the college was fortified by Parliamentarian forces. In 1685, Monmouth's rebellion involved Robert Sewster, a fellow of the college, who commanded a company of university volunteers, mostly from New College; they exercised on the bowling green.[20]

Academic

[edit]Students at New College were until 1834 exempt from taking the university's examinations for the BA and (in earlier times) the MA degrees, and were also ineligible for honours, though they still had to take the college's own tests. The college used to have a reputation for "Golden scholars, silver bachelors, leaden masters and wooden doctors."[21] More recently, like many of Oxford's colleges, New College admitted its first mixed-sex cohort in 1979, after six centuries as an institution for men only.[22]

In 2022, students at New College scored 75.5 on the Norrington Table.[23]

The choristers were originally accommodated within the walls of the college, under one schoolmaster. Since then the school has expanded; in 1903 the choristers moved to New College School in Savile Road.[24]

College links

[edit]King Henry VI is said to have established his own new colleges, King's College, Cambridge, and Eton College, either in admiration of William of Wykeham's twinned institutions of New College and Winchester College, or at least to have modified his plans to outdo them.[25][26]

New College and Winchester College have from the mid 15th century been formally linked to Eton College and King's College, Cambridge, a four-way relationship known as the Amicabilis Concordia.[27][28] King's and New College are sister colleges.[29]

Buildings and gardens

[edit]At the time of its foundation, the college was a grand example of the "perpendicular style".[30] With the evolution of the college over the centuries, it has regularly added to its original quadrangle. The upper storey of the quad was added in the sixteenth century as attics which, in 1674, were replaced by a third storey proper as seen today. The oval turf at the centre of the quad is an eighteenth-century addition.[30] Many of its buildings are listed as being of special architectural or historical importance.[a]

The initial building phase saw the construction of the Great Quad with the Gate Tower, the dining hall with the four-storeyed Muniment Tower for access, the chapel, the cloisters (consecrated as a burial site in 1400) with the four-storeyed bell tower (1400), along with the Warden's Barn in New College Lane (1402) and the Long Room (behind the SE corner of the Great Quad), purpose-built as a garderobe.[31]

The three-sided Garden Quadrangle, open at one end and begun by the addition of The Chequer to the east of the Great Quad in 1449, was completed in two stages between 1682 and 1707. Further college expansion led to the formation of Holywell Quad in the 19th century. A range known as 'New Buildings' was built along Holywell Street between 1872 and 1896, partly by George Gilbert Scott in High Victorian style (1872), and partly, including the Robinson Tower over the entrance gates, by Basil Champneys in late Victorian style (1885, 1896).[32][33]

New College is building a new development on its Savile Road site, next to New College School. The Gradel Quadrangles were designed by David Kohn Architects and received planning permission in June 2018. They will provide an additional 99 student rooms, additional dining and kitchen space, a flexible learning hub and a performance venue.[34] In 2022, Sir Robert McAlpine was proceeding with construction.[35]

-

Photo-chrome of Garden Quad

-

Holywell Street: Scott Buildings and Robinson Tower

-

The Chapel and old city wall from Holywell Quad

-

Front Quad

-

Gradel Quadrangles, Mansfield Road, nearing completion, March 2024

Hall

[edit]The hall is the dining room of the college and its dimensions are eighty feet by forty feet (24 m × 12 m). In his charter, Wykeham forbade wrestling, dancing and all noisy games in the hall due to the close proximity of the college chapel and the lodgings below the hall; he further prescribed the use of Latin in conversation.[30] The linenfold panelling was added while Archbishop Warham was bursar. The floor was paved with marble in 1722. By the end of the 18th century, the open oak roof had been replaced by a ceiling. When the Junior Common Room offered £1000 to restore the hall roof, work began in 1865 under the architect George Gilbert Scott to create the current roof. The plain windows were replaced with stained glass, and the portraits were relocated.[30] The hall underwent a major restoration project in 2015.[36]

-

Hall

Chapel & cloisters

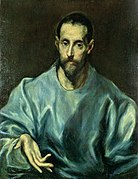

[edit]The chapel was based on the plan of Merton Chapel.[37] The transepts and tower that made Merton Chapel T-shaped were omitted, and a screen separated the main chapel from the ante-chapel. The medieval interior was modified after the Reformation, with the removal of secondary altars, the rood loft, and the reredos' statues, the reredos being covered in plaster.[38] Much of the medieval stained glass in the ante-chapel was restored in a 20-year project which was commended in the 2007 Oxford Preservation Trust Environmental Awards.[39] The chapel contains a statue of Lazarus by Sir Jacob Epstein[40][38] and a painting by El Greco.[41][42] Some of the stained glass windows, including the Great West Window, were designed by the 18th-century portraitist Sir Joshua Reynolds.[41]

-

Chapel reredos

-

The Chapel, looking towards the altar

The choir stalls contain a "splendid set"[38] of 62 14th-century misericords.[17][43] The niches of the reredos, which had been plastered over, were uncovered in the 1780s, and were fitted with statues by Sir Gilbert Scott in the late 19th century.[44] The chapel preserves the Founder's Crosier, a bishop's staff decorated with enamel and silver gilt; it resembles a crosier at Cologne Cathedral.[41][45]

The cloisters, containing a large holm oak tree, sit by the western wall of the Chapel, were featured in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, in the scene in which Draco Malfoy is turned into a white ferret.[36] Michael Darbie recast the original five bells of the bell tower into eight in 1655, creating the first set of eight to be cast simultaneously.[46] In 1712, two more bells were added, supposedly to outmatch Magdalen College's new ring of eight bells created in that year.[46][47] The bells are rung by the Oxford Society of Change Ringers.[46]

-

The Cloisters, exterior

-

The Cloisters, interior

-

Drawing of the Cloisters and Chapel

Gardens and city wall

[edit]The Middle Gateway opens to the Garden Quadrangle.[48] The gardens include a mound that was first arranged in 1594 (with steps added in 1649,[49] but now smooth with one set of stairs). In a 1761 edition of Pocket Companion for Oxford the mound is described:

- "In the middle of the Garden is a beautiful Mount with an easy ascent to the top of it, and the Walks around it, as well as the Summit of it, guarded with Yew Hedges. The Area before the Mount being divided into four Quarters, [..] the King's Arms, [..] opposite to it the Founder's; in the third a Sun Dial; and the Fourth, a Garden-Knot, all planted in Box, and neatly cut."

When William of Wykeham acquired the land on which to build the college, he agreed to maintain the city wall.[50] The herbaceous border that runs alongside the wall is mentioned in Historic England's listing of the garden.[51]

-

The Gate in Garden Quad

-

Old city wall in the College gardens

-

The Garden Mound

Sports ground

[edit]The New College sports ground south of the University Parks was established in the 1880s.[52][53] The Weston buildings, which accommodate postgraduate students, were built next to the ground in 1999.[54]

Treasures

[edit]The college treasures include paintings and a substantial silver collection.[40] The library contains a copy of the first printed edition of Aristotle.[30] A Barbara Hepworth statue stands by the City Wall.[36]

Music

[edit]Choir

[edit]

In 1379, William of Wykeham provided for a choral foundation of clerks and boy choristers.[55] The tradition continues today with choral services during term.[56] The choir often performs Renaissance and Baroque music, including Handel's works.[57] As well as appearing repeatedly at the BBC Proms, the choir has made numerous concert tours.[58]

The choir has recorded over one hundred albums.[59] In 1997, the choir won a Gramophone Award in the best-selling disc category for their album Agnus Dei,[60] and in 2008, they won a Gramophone Award in the early music category for their recording of Nicholas Ludford's Missa Benedicta.[61] On 29 June 2015, at the invitation of the Holy See and the Cappella Musicale Pontificia Sistina, the choir sang at the Papal Pallium mass for the Solemnity of Saints Peter and Paul in St. Peter's Basilica.[62][63][64]

Organ

[edit]The original organ was given by William Porte (1420–1423).[65] An organ was removed in 1547 under Edward VI, and likewise in 1572.[66] A Willis organ installed in 1874 contained parts from organs by Samuel Green in 1776, James Chapman Bishop, and Dallam in 1663.[67]

The present instrument was constructed by Grant, Degens and Bradbeer in 1969.[68] In 2014 the organ was restored, with the key actions and other mechanisms being completely renewed by Goetze and Gwynn.[69]

-

The organ, between the chapel and the ante-chapel

Student life

[edit]

Outreach

[edit]New College has launched Step-Up, a sustained contact outreach initiative which seeks to inspire students from partner schools in England and Wales to apply to Oxford and supports them to make a competitive application.[70] The college founded the Oxford for Wales consortium, Oxford Cymru, along with Jesus College and St Catherine's College, offering support to students from state schools in Wales.[71]

Rowing

[edit]A New College rowing eight is recorded from 1840; the New College Boat Club was "Head of the River" in Eights Week in 1887 and several years from 1896. The club headed the Torpids competition in 1882, 1896, and 1900 to 1904.[72] The club represented Great Britain at the Summer Olympics in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1912, and earned a silver medal.[73]

People associated with New College

[edit]Science

- Marc Tessier-Lavigne, Canadian-American neuroscientist who was the eleventh president of Stanford University

- Pardis Sabeti, American computational biologist, medical geneticist, and evolutionary geneticist

Politics

- Susan Rice, American diplomat, policy advisor, and public official

Organisation and administration

[edit]The head of the college is the warden, who is responsible for academic leadership, chairs the governing body, and represents the college. Policy is defined and actioned by the warden together with the fellows of the college,[74] who are scholars.[75] New College is one of the constituent self-governing colleges of the University of Oxford, which has a federal organisation.[76] The warden is supported by specialist officers including tutors, bursar, librarian, and chaplain.[74][77]

The students are divided into a Middle Common Room consisting of the college's graduates, and a Junior Common Room for the undergraduates; these are run by their own committees.[78][79]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Buildings listed as being of special architectural or historical importance by the public body Historic England:

- Historic England. "WALL, SOUTH OF BASTION 15 (1369707)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Historic England. "WALL TO EAST OF BELL TOWER (1046610)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Historic England. "BASTION 12 IN NEW COLLEGE (1046611)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Historic England. "BASTION 13 (1046612)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Historic England. "WALL SOUTH OF BASTION 14 (1046613)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Historic England. "NEW COLLEGE, WEST RANGE, GREAT QUADRANGLE (1046686)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Historic England. "NEW COLLEGE OXFORD, CLOISTER (TO WEST OF CHAPEL) (1046687)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Historic England. "NEW COLLEGE, NORTH RANGE (1046688)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Historic England. "NEW COLLEGE, IRON SCREEN (1046689)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Historic England. "NEW COLLEGE, TUTORS HOUSE (TO THE EAST OF THE PANDY) (1046690)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Historic England. "WALL TO EAST OF BASTION 11 (1184453)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Historic England. "WALL EAST OF BASTION 12 (1184468)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Historic England. "BASTION 14, ON NORTH EAST ANGLE OF WALL (1184494)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Historic England. "BASTION 15 (1184504)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Historic England. "NEW COLLEGE, SOUTH RANGE, GREAT QUADRANGLE (1200417)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Historic England. "NEW COLLEGE, NORTH RANGE HALL, KITCHEN AND CHAPEL, GREAT QUADRANGLE (1200433)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Historic England. "NEW COLLEGE, BELL TOWER (1200452)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Historic England. "NEW COLLEGE, BOUNDARY WALL FRONTING NEW COLLEGE LANE AND QUEENS LANE (1300694)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Historic England. "NEW COLLEGE, NEW BUILDINGS (1300697)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Historic England. "NEW COLLEGE, SOUTH RANGE (1300731)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Historic England. "NEW COLLEGE, EAST RANGE, GREAT QUADRANGLE (1369665)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Historic England. "NEW COLLEGE, THE WARDENS BARN (1369666)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Historic England. "NEW COLLEGE, THE LONGHOUSE (1369667)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Historic England. "BASTION 11 (1369705)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Historic England. "WALL, EAST OF BASTION 13 (1369706)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Historic England. "WALL, SOUTH OF BASTION 15 (1369707)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

References

[edit]- ^ "Colleges of St Mary Winton Collection". New College, Oxford. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

Cartae de Fundatione Collegii Beatae Mariae Wynton in Oxon, A.D. MCCCLXXIX (1879)

- ^ "College Officers". New College, Oxford. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ a b "About Us". New College, Oxford. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ "New College: Annual Report and Financial Statements: Year ended 31 July 2021" (PDF). ox.ac.uk. p. 10. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ "New College: University of Oxford". www.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "Statutes Made for the College of Saint Mary of Winchester in Oxford, Commonly Called New College, in Pursuance of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge Act 1923" (PDF). New College. 2016.

His statutes provided for a college comprising a warden and 70 fellows, both graduates and, a novelty at the time, undergraduates.

- ^ a b c d "The History of New College". New College. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ a b Prickard 1906, pp. 68–69.

- ^ "The history of New College". New College - Oxford. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ Prickard 1906, p. 17.

- ^ Prickard 1906, pp. 25–26.

- ^ "Winchester College: Heritage". Winchester College. Archived from the original on 26 January 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ^ Hayter, William Goodenough (1970). William of Wykeham: Patron of the Arts. London: Chatto & Windus. p. 75.

- ^ Prickard 1906, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Prickard 1906, p. 22.

- ^ "History of Oxford New College School". Of Choristers – ancient and modern. Archived from the original on 9 January 2005. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- ^ a b c Salter, H E; Lobel, Mary D., eds. (1954). "New College". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 3, the University of Oxford. London: Victoria County History. pp. 144–162.

Most previous colleges had been designed to enable graduates to proceed to higher degrees. New College was primarily designed to take undergraduates through their arts course;

- ^ Salter, Herbert Edward (1936). Medieval Oxford. Oxford: Oxford Historical Society. p. 97.

I estimate that in 1360 the six colleges which then existed would contain about 10 undergraduates, 23 bachelors and 40 masters.

- ^ Cobban, Alan B. (2017). The Medieval English Universities. Taylor & Francis. p. 122. ISBN 9781351885805.

prior to the virtual doubling of the number of fellowships with the foundation of New College in 1379, the six secular colleges supplied a total of only about 63 graduate fellows.

- ^ Prickard 1906, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Prickard 1906, pp. 52–54, 57.

- ^ "The History of New College". New College. Archived from the original on 13 April 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ "Undergraduate Degree Classifications | University of Oxford". www.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ "New College School, Oxford". Archived from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- ^ Prickard 1906, p. 62.

- ^ "Travel Through History — Henry VI". Archived from the original on 26 October 2007.

- ^ "King's College Publication Scheme". King's College, Cambridge. Archived from the original on 28 September 2006.

- ^ Prickard 1906, p. 61.

- ^ "King's College". Cambridge Colleges. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Prickard 1906, pp. 26–32

- ^ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 166-169, 172-173.

- ^ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 173-174.

- ^ "Our living heritage". New College. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ "The Gradel Quadrangles". New College. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ "Richard Bayfield, Project Director, New College, talks about the collaboration with Sir Robert McAlpine". Sir Robert McAlpine. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ a b c "Our Buildings". New College. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 169.

- ^ a b c Goodall, John (4 November 2019). "New College, Oxford: The 650-year story of the college that dreamt it was a palace". Country Life. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ "Glazier's Magnificent Seven". oxfordtimes.co.uk. 8 February 2008. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- ^ a b "College Treasures". New College Oxford. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ a b c "New York Times Guide". The New York Times. 9 May 1982. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ "Treasures and Chattels Gallery". new.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ^ "The Elaine C. Block Database of Misericords". Princeton University. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ The Chapel Reredos (PDF). New College. pp. 1–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 June 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ Prickard 1906, p. 39.

- ^ a b c "New College". Oxford Society of Change Ringers. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ "Oxford, Oxfordshire, New College". Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ Prickard 1906, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 174.

- ^ Prickard 1906, p. 53.

- ^ "New College". Historic England. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

Official list entry Heritage Category: Park and Garden Grade: I List Entry Number: 1001100 Date first listed: 01-Jun-1984

- ^ Ranjitsinhji, K. S. (1897). The Jubilee Book of Cricket. Good Press. p. 318.

- ^ Prickard 1906, p. 89.

- ^ Graham, Malcolm (2015). Oxford Heritage Walks Book 3 (PDF). Oxford Preservation Trust. p. 18. ISBN 978-0957679726. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ "About Us". New College Choir. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

When William of Wykeham founded his 'New' College in 1379, a choral foundation was at its heart, and daily chapel services have been a central part of college life ever since. The Choir comprises sixteen boy choristers and fourteen adult clerks;

- ^ "The Chapel and Choir". Archived from the original on 29 December 2008.

- ^ Stevenson, Joseph. "Edward Higginbottom". Allmusic.com.

- ^ "The Choir of New College Oxford". Archived from the original on 7 March 2009.

- ^ "Shop". newcollegechoir.com. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

- ^ "Excerpts From The 1997 Gramophone Award Winners". Discogs. 1997. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

9 Rachmaninov– Agnus Dei: Choir – Choir Of New College, Oxford: Composed By – Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninoff; Conductor – Edward Higginbottom

- ^ "Gramophone classical Music Awards 2008: Early Music". Gramophone. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

Ludford – Missa Benedicta: Choir of New College, Oxford / Edward Higginbottom: K617 206

- ^ "Pope welcomes Orthodox delegation for feast of Sts Peter and Paul: Choristers of the Anglican choir of New College, Oxford, sing during Mass". Efpastoremeritus2. Archived from the original on 13 August 2015. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ^ Glatz, Carol (30 June 2015). "Archbishops who attended pallium Mass struck by sense of unity". Catholic Herald. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ^ "Papal Pallium Mass – St. Peters Basilica". allevents.in.

- ^ Prickard 1906, p. 36.

- ^ Nicholas Tyacke, ed. (1997). The History of the University of Oxford: Volume IV: Seventeenth-Century Oxford. Clarendon Press. p. 627. ISBN 0199510148.

- ^ Prickard 1906, p. 35.

- ^ Organ, New College Choir Archived 25 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 1 May 2010

- ^ "News & Events – Choir of New College Oxford". newcollegechoir.com. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ "Step Up". New College. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ "Oxford for Wales". New College. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ "Our History". New College Boat Club. 17 January 2022. Archived from the original on 24 April 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ "The Fifth Olympiad – Official Report of the Olympic Games of Stockholm 1912 (Swedish Olympic Committee 1913) pp.662–667". 1913.

- ^ a b "College Officers". New College, Oxford. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ "The Fellows". New College, Oxford. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ "Organisation". University of Oxford. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ 'New College', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 3: The University of Oxford (1954), pp. 144-162 online at british-history.ac.uk, accessed 26 August 2008.

- ^ "New College MCR". New College MCR. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ "New College JCR". New College JCR. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

Sources

[edit]- Buxton, John, and Penry Williams (1979). New College, Oxford, 1379–1979. Oxford: Warden and Fellows of New College. ISBN 978-0950651002.

- Halford Smith, Alic (1952). New College, Oxford, and its Buildings. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jenkinson, Matthew (2013). New College School, Oxford: A History. Oxford: Shire. ISBN 978-0747813415.

- Prickard, Arthur Octavius (1906). New College, Oxford. London: J.M. Dent.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2010). New College. London: Third Millennium. ISBN 978-1906507213.

- Sherwood, Jennifer; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1974), Oxfordshire, The Buildings of England, London: Penguin, ISBN 0300096399

External links

[edit]- New College, Oxford

- 1379 establishments in England

- Educational institutions established in the 14th century

- Colleges of the University of Oxford

- Grade I listed buildings in Oxford

- Grade I listed educational buildings

- Organisations based in Oxford with royal patronage

- Buildings and structures of the University of Oxford